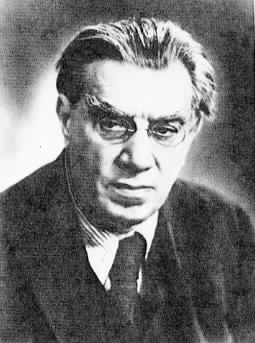

Reinhold M. Glière* January 11, 1875 in Kiev

|

|

Composer and Music Teacher . |

|

|

|

|

|

Reinhold Moritsevich Glière, second son of Ernst Moritz Glier and Josephine Kortschak was born 1875 in Kiev. In some musical dictionaries, books and CD-booklets he is said to be "son of jewish parents from belgian decent". This is obviously wrong! Reinhold Glier was born on December 30, 1874 (old calendar) and was baptized on January 19, 1875 in the Protestant Lutheran Church of Kiev by Preacher O. Koenigsfeldt. A copy of the bilingual (Russian / German) baptizing certificate is published by Gulinskaya [1]. The French notation of the name is authentic, however, has nothing to do with the descending (see: spelling). His father was born in Klingenthal /Saxony /Germany, where his family had lived for centuries. He was a successful instrument maker, specializing in work on wind instruments. Reinholds mother, Josephine Kortschak, was the daughter of a Polish instrument maker. Stanley D. Krebs [2], who also subscribes to the jewish belgian extraction, believes that Gliere's parents were not enthusiastic about their children following musical careers and wanted their son to be a doctor or engineer, but class and race restrictions militated against them. Perhaps the Saxon ancestry imposed the same restrictions. Despite all Reinhold wished to be a musician and he made his first tentative efforts at composition at the age of fifteen.

Gliere began studying violin at an early age with Adolf

Weinberg (1844 - 1921),

and soon his prodigious musical talent was revealed. At the age of ten he entered

in Kiev the high school and soon after the music school, where he started

studies in the violin. Studying concurrently in the high school and music school, he

successfully took and passed courses in theory and composition (with

Rimsky-Korsakov student E. A. Ryb), in piano, and especially in violin. His

achievement in the latter was great and everything indicated, that he should

continue in the Moscow conservatory.

| In 1894 Reinhold Glier moved to Moscow and entered the Conservatory as a violin

student under Ivan

W. Grzhimali. He indulged his interest in composition from the

first, however, studying harmony with Anton S. Arensky (1861-1906) and Georgii E. Konius (1862-1933), polyphony

with Sergei I. Taneev, and composition with Michael M. Ippolitov-Ivanov. Gliere himself felt

that Taneev played the central role in forming his creative outlook,

but his music does not reveal this. Gliere, however, later fastened on

Taneev as a model for teaching. Gliere graduated in

1900 with the gold medal in composition, the conservatory's highest award.

By this time he had already completed an opera (his thesis Earth and Heaven), his

first quartet, an octet and his first symphony (op.8).

|

|

Two students were referred to him by Taneev in 1900. Both were ineligible for entrance to the conservatory, Miaskovsky because of his army obligations and Prokofieff because of his youth.

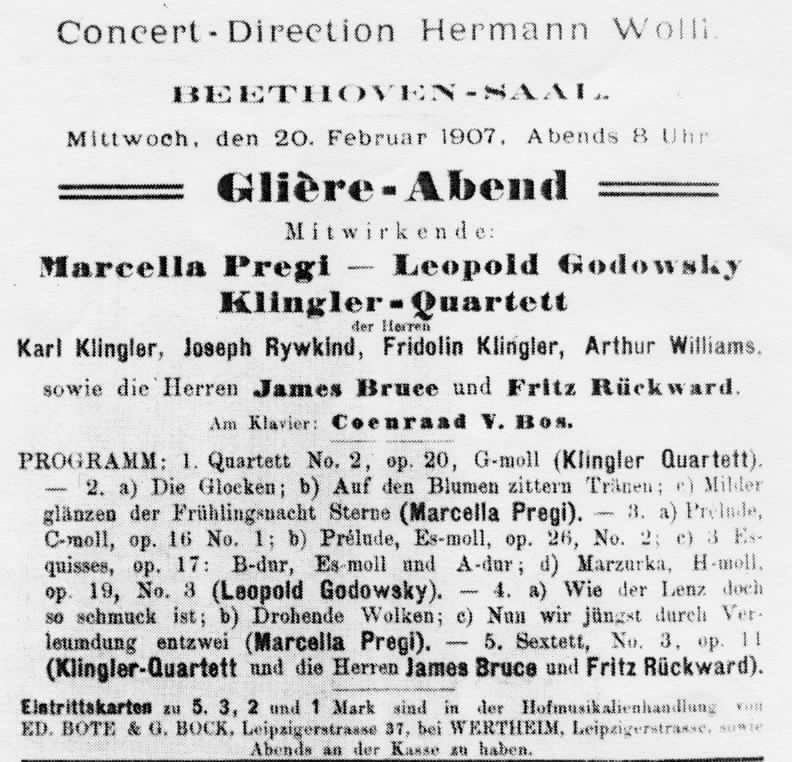

On April 21, 1904 Reinhold Glière married Maria Robertowna Renkvist. The couple had five children: 1905 the twins Lia and Nina, 1907 a son Robert and 1913 another twins Leonid and Walja. In 1905 Gliere left for Berlin for further study. He was well respected and well received in Berlin; his second symphony was premiered there on January 23, 1908. In 1907 Gliere began intensive study of conducting under Oskar Fried.

|

|

Upon his return to Russia he embarked on a short-lived conducting career. In 1913 the Kiev music school was upgraded by the Imperial Russian Music Society (IRMS) to a conservatory, and Gliere joined the staff. In 1914 Gliere became director of the conservatory and continued in that post until he left for Moscow in 1920. He was instrumental, therefore, not only in establishing the new conservatory, but in implementing its transition from an IRMS to a Soviet institution. Gliere's return to Kiev may be considered symbolic of his extreme traditonalist turn about this time. It is said that Glière was one of the first big composers responding to the call of Soviet power and assuming his stand in the ranks of builders of Soviet musical culture. Actually, and again this must be emphasized in connection with most of the older generation of composers, Gliere was apolitical and conservative in the cause of music. He had little part in the various musico-political groups of the early Soviet Union. Since all these foundered, it has made of him, in retrospect, a hero today. However, at the time, he was criticized for his lack of interest and lack of political direction.

In 1920 Gliere became a professor of composition at the Moscow Conservatory, continuing in that post until the outbreak of the Second World War. His creative attention had turned to the stage as late as 1917; until then be had but one opera (Earth and Heaven, 1900) and one ballet-pantomime (Khrisis, 1912) to his credit. Of the three ballets written during the twenties, Komedianty (written in 1922 but not performed until 1930 after extensive revision), Cleopatra (1925), and the Red Poppy (1926 / 27), it was the latter that would be hailed as the foundation of Soviet opera. The story involves revolutionary activity in China. His last symphony, the symphony Ilya Muromets (symphony no. 3 op. 42) was finished in 1911. It bases on the legend of "Ilya Muromets", a legendary Russian hero from an old Russian epic poem. The history is found in many Russian poems.

| In 1923 Gliere was invited to Azerbaidzhan to

help in the "Soviet development" of that country. The result of his

journey was the opera Shakh-Senem, a work that contained many elements of

Azerbaidzhan folk music.

The first performance took place in Baku in 1927, though in Russian language. A

second version in Azerbaidzhan language was performed 1934 in Baku. Glière

remained in Azerbaidzhan from 1923 to 1924 and returned for an extensive stay in

1929.

All independent cultural organizations were disbanded by party and state. Gliere and others "old masters", e.g. Ippolitov-Ivanov and Mjaskovski, were attracted of this and agreed. The Moscow composers founded the association of Soviet composers whose executive boards Glière entered in summer 1932. |

|

In this time of radical changes in the music of the Soviet Union, Reinhold Glière got the message that his elder brother Moritz had passed away in Dresden /Germany. Since Moritz didn't have any heirs, the inheritance (among other things a ground property) was left to the surviving mother Josephine and his younger brother Karl, who lived in Germany since 1920. At that time it was not good for the reputation of a Soviet composer to be a land owner in Germany. In a letter to his brother Karl he declined the inheritance, but the letter was insufficient for German land register officials to make the necessary entries. The transfer wasn't recorded in the land register and after the German political change in 1989 living relatives noticed that the DDR government had sold the property because of "owner not discovered".

|

|

Gliere moved away from opera and ballet in the thirties,

but not from the stage and screen. His activity during this period was

in the dramatic theatres, where he wrote incidental music to seven plays

and in films. Gliere's attention also turned to more "social"

music. During this period he wrote the Festival Overture to commemorate

the twentieth anniversary of the revolution in 1937; Fergana Holiday, dedicated

to the construction, then in progress, of the Stalin Fergana canal (using

Uzbek and Tadzhik themes); the Friendship of Peoples Overture, celebrating

the fifth anniversary of the Stalin Constitution; and the Heroic March

of the Buriat-Mongol Autonomous Republic. With the beginning of the World War II,

the aging composer's teaching was interrupted and was never to continue. Under the Soviet system of rewards and punishments for

artistic activity, Gliere was one of the most honoured of Soviet composers.

He became a People's Artist of the Azerbaidzhan SSR in 1934, of the RSFSR

in 1936, of the Uzbek SSR in 1937 and, finally, of the Soviet Union in

1938. He was awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labour in 1937 and

the Order of Honour in 1938. Later, Gliere was to receive three Orders

of Lenin (1945, 1950, 1955 - these are usually birthday honours) and three

first-degree Stalin Prizes (1946 - Concerto for Voice and Orchestra, 1948

- Fourth String Quartet, and 1950 - The Bronze Horseman, a ballet).

|

From 1939 - 1951 Gliere wrote

four concertos, which have had a considerable impact on Soviet music. These

were for harp (opus 74, 1939), Coloratura soprano (opus 82, 1942 / 43), cello

(opus 87, 1947) and French horn (opus 91, 1951). The cello concerto

was a significant milestone: this is not only the first Soviet cello concerto, but the first Russian

cello concerto. The work is dedicated

to Mstislav Rostropovich, who's thirst for

new music was insatiable. Gliere was approached by the cellist and so he helped

to augment the cello literature of that time; and this is largely due to

the demand of Rostropovich. The

Gliere harp concerto was also unusual in its choice of instrument, and

also was a refreshing exercise in orchestral economy. Whereas the cello

concerto used an augmented orchestra, the harp work is supported by an

orchestra of near chamber size.

Gliere returned to opera and ballet after a ten-year break. Working as co-author with Talib Sadykov, Gliere's student at the conservatory Uzbek Studio, he wrote two operas: Leili and Medzhnun and a Russified version of Giul'sara for the operatic stage. In 1942 / 43 he wrote the opera Rachel, based on de Maupassant's "Mademoiselle Fifi". He returned to the ballet genre with The Bronze Horseman (1948 / 49) and Taras Bul'ba (1951 / 52). His last ballet was Daughter of Castille (1955) after Lope de Vega. The Bronze Horseman was often performed. The libretto of the piece is based on Pushkin's poem of the same name and contains episodes of two other Pushkin poems: "The Little House in Kolomna" and "The Blackamoor of Peter the Great".

Gliere was scarcely mentioned in the 1948 blanket condemnation of prominent composers. His health had been declining in the last few years, and his teaching career had long since ended, though he occasionally appeared for a conservatory master class. Although he continued working until the end of his life, his output in the last years was, for him, relatively small.

|

|

|

Much of the time from 1948 on was spent at the Moscow Union of Soviet Composers' rest and recreation resort at Ivanovo, where the "older" generation tended to gather. He saw a great deal of his two first students, Miaskovsky and Prokofi'ev, before their deaths in 1950 and 1953, respectively. Reinhold Gliere died in Moscow on June 23, 1956.